by Napoleone Ferrari

Historians had and still have difficulty in positioning Carlo Mollino within art and architecture history. Mollino never belonged to any group or art movement and categorizing Mollino’s work is, in fact, a problematic undertaking due to the eclecticism of his work, which over time also evolved in different directions.

We recognize a Futurist and at the same time a decadent Mollino, an engineer and a Surrealist, a sensual spirit and a modern brutalist... Whichever definition well suits one of his works may then not be valid to describe another; in actual fact, in order to appropriately define Mollino’s oeuvre, we should make clear to which part of it we are referring.

Nevertheless, it is possible to recognize and analyze an evolving process in his work and we can certainly acknowledge specific qualities and ways of thinking pertaining to Mollino’s personality. Defining Mollino’s contribution to modern architecture remains an intriguing rebus, reflected also by the quite dissimilar interpretations given to his work by different scholars so far.

ITALOMODERN

During his university years and after graduation in 1931 Carlo Mollino continued to work under the firm guidance of his engineer father, thus laying the foundations for his precise mastery in construction techniques: he was able to draw in detail a door or a window; the structure of a roof or a staircase; a plumbing system... With this rich technical background, in 1933 he designed his first building and at the same moment began speculating on the position of a debuting young architect onto the contemporary architectural scene. Speaking of Oberon, his fictitious autobiographical character, Mollino wrote:

“Some wished to see points of contact between Oberon and Sant’Elia but we would discount all possible parallels: Sant’Elia had prophetic virtues and perhaps those of the genius whereas Oberon arrived after the show had started and the outcomes were inevitable."[^]

With this, Mollino meant to say that the pioneering times of the ‘Modern’ had already passed and modern architecture had already been invented by the time he arrived on stage. Hence his first building design earnestly complied with the Modern Movement although it was already characterized by an exuberant movement of its volumes and other qualities that were germs of his forthcoming personal style.

Speaking of Italy, in the 1930s the architecture and art scene could be roughly described as being divided among four different groupings: the dominant Fascist classicism of the Novecento art movement and the related classicism of the regime architects led by Marcello Piacentini; Second Futurism; the Metaphysical; and the avant-garde of MIAR (Italian Movement for Rational Architecture).

Mollino did not adhere to any of these movements nor did he take part in their mutual polemics, even though one can recognize a certain empathy for Futurism[^] and the Metaphysical[^]. For the rest of his life he did not adhere to any art movement nor did he pretend to theorize one; rather, he followed, or built, his own path, believing in and supporting individual differences.

EXPRESSIONISM OR SURREALISM

One of the coordinates that define Mollino’s work can be found at the intersection between Expressionism and Surrealism. The experience he had in the summer of 1931 in the Berlin studio of Erich Mendelsohn,[^] the master of Expressionism, was duly reflected in Mollino’s 1933 project for the Farmers’ Federation.

In August 1934, with the publication of his second novel “L’amante del Duca” (The Duke’s Lover), the Surrealist influence clearly manifested itself for the first time in a moment in which Mollino already had access to Minotaure magazine (his dear friend Albino Galvano noted[^] the presence in Mollino’s library of all 13 issues of Minotaure, published between June 1933 and May 1939).

Both Expressionism and Surrealism considered emotion to be an essential function of a building or an artwork, which radically broadened the common meaning of what was considered functional. Both movements defended the uniqueness of an individual or of a place rather than pushing toward international standardization. Both used symbols as linguistic devices in order to sublimate and amplify the objective data of reality. Both referenced the principles of Freud and Jung, who set the psyche and the unconscious at the center of their investigations.

All Mollino’s work, from 1933 to 1973, was intimately linked to these inclinations, yet Surrealism undoubtedly stood out as the strongest[^] (most evidently in his 1930s works: Casa Miller; Casa Devalle; B&W architecture photos and women’s portraits; Horse Riding Club).

In general, his work was tinged with dreamlike and fairy-tale qualities; he made extensive use of historical quotes and pairings of surprisingly contrasting elements; and he was often in search of sensual even erotic softness and elegant lightness, a combination of features not properly Expressionist.

Another significant element of his work can be traced to Magic Realism, a literary declination of Surrealism of which the Italian Massimo Bontempelli was a pioneering figure, and among Mollino’s readings.[^] Besides writing two novels himself, Mollino enriched his architectural work with a sometimes surprising sense of narrative.[^]

What makes Mollino’s Surrealism particularly relevant is that it was expressed by a person highly acquainted with technology and the sciences; in fact, he often successfully founded his poetics by impeccably synthesizing rational with expressive elements.

ECLECTIC LANGUAGE

As mentioned above, Carlo Mollino was well aware of the fact that the invention of Modern architecture had been made before his arrival on the scene, yet this ‘delay’ allowed him a wider perspective on history, positioning him in the mindset of what he himself called Eclecticism.[^]

Mollino explicitly articulated this cultural position for the first time in 1943[^]: it was a matter of harmonizing instead of opposing the various ‘isms’ that characterized the Modernist family, but it was also about harmonizing the modern with the antique.

When Mollino wrote “humans matter only insomuch as they contribute to a historic process; outside of history, humans are nothing,”[^] he also implied gratitude for history, then generating that peculiar pleasure he always took in quoting the past[^] in the most varied and unexpected forms.

Mollino considered architecture a linguistic system,[^] therefore being eclectic meant considering the different styles and the different building techniques, past and present, as a great vocabulary to draw upon. He envisioned a synthetic and non-syncretistic Eclecticism,[^] far differing from deleterious forms of 19th-century Eclecticism which he considered still alive in modern times.

A consequence of this way of thinking was the possibility of using different architectural tools at the same time when confronting different architectural problems: the Chamber of Commerce and the Regio Opera House projects are excellent examples in this sense; built at the same moment, they seem designed by two different architects.

Typical of Mollino was a non-ideological approach to architecture, a relativism that led him to write:

“Any disputes that may arise between organic architects and functional architects, and in the past between functionalists, rationalists, and classicists, are of purely historical and contingent worth. Poetry can sit very well on one side or the other.”[^]

The word ‘eclectic’ evoked a lack of coherence and a negative quality. Nonetheless, Mollino felt in good company on the road to “the newly eclectic contemporary taste,”[^] together with artists such as Picasso, Stravinsky, Le Corbusier, Joyce, and Man Ray.

ORGANIC: THE ENGINEERING OF LIFE

In 1941, when working on an essay about the engineer Alessandro Antonelli (1798-1888), Mollino opened a new perspective in his research:

“Think of the internal structure of the upper epiphysis of a human femur. Simply consider the difference that still exists between the fuselage of a glider and a heron’s ribcage: an integral of precision, matter brought together where needed and in no more measure than strictly necessary; maximum force and minimum weight: elegantia.”[^]

This essay was pivotal in Mollino’s oeuvre, initiating a long-lasting interest for structures made by nature as being the most effective: beautiful and functional.

So he began to introduce shapes and organic-like structures derived from nature into his architecture and furniture design, where it is most easily recognizable in the latter. Starting from the experience of Art Nouveau, the work of Antoni Gaudì, and the thinking of Henry Van de Velde,[^] it is possible to follow a precise development in Mollino’s furniture design, year by year, from the 1943 Garzanti competition, to the 1944 Casa Albonico, the 1945 Casa Minola… until 1953, when Mollino considered his research substantially accomplished and halted this process.

He developed his designs departing from a seemingly vitalistic approach in which forms followed the lines of force of the ‘field’ of a living creature in a synthesis between the anatomical studies of Julius Wolff[^] and the philosophy of Henry Bergson, initially resulting in highly carved organic sculptural furniture.[^] He then gradually moved toward a simplification and a more linear adherence to the essence of structures, ultimately using bent plywood.

In his furniture and architecture designs Mollino was able to combine rigorous and rational construction systems together with amazingly expressive qualities. When at his best, he succeeded in designing three-dimensional bodies entrusted with a logical internal structure and with the dynamic tension of living creatures. This is how Mollino updated Art Nouveau to the Modern Movement.

Beautiful and functional… without forgetting, however, that the difference between the beauty of Nature and that of Art remains unbridgeable, which Mollino expounded upon using the words of Goethe:

“Art only exists in its own history: in every era, every people has its own; it is the ‘Stimmer der Völker,’ the voice of the people… and Goethe was the first to move beyond the traditional Apollonian and hedonistic concept of beauty: ‘Beauty is revealed by character and from such character it emerges like a plant from its seed.’”[^]

THE MOVING ARABESQUE

A Futurist lineage is undoubtedly present in Carlo Mollino’s work.[^] We can observe this in his first designs (Farmers’ Federation, Casa Miller) but also later (apartment building in Sanremo, Fürggen Cable Car Arrival Station); and, in general, we can say that Mollino sought for dynamism and movement in a similar way to the Futurist sculptors and painters. Equally, Mollino was fascinated by the ‘machine,’ which is most evident in his technical activities related to skiing, cars, airplanes, and photography.

Yet it looks as though he dealt with movement and machines in a rather multidimensional and much broader way than the Futurist artists usually intended: ‘machines’ for Mollino were not only mechanical but also the organic ones produced by nature, while Surrealism led him to consider movement as a process that was not only physical or sensory but also psychological and related to time.

A word that consistently recurs in Mollino’s writings, arabesque, can help us focus on a more complex consideration of movement. For Mollino, an arabesque is a curved line, eminently the Art Nouveau[^] whiplash, which we characteristically find in most of his projects and which we can also immediately spot in his sporting endeavors, such as skiing or flying. In fact, an arabesque directly links these last activities, apparently just hobbies, to his work:

“Those who know me recognize that I do not do aerobatics out of vanity, but as a sport designed to attain harmony in the conscious use of meticulous control. This passion is closely connected to my profession and, as a matter of principle, excludes any desire for thrills, risk or exhibitionist daring.”[^]

The arabesque lines drafted with a plane in the sky or on the snow with skis are the outcome of a rigorous exercise: a balance between the technical and physical possibility of movement, with certain skis or with a certain plane, and a harmonious way of performing this movement. It is a challenge against the law of gravity to achieve naturally beautiful movements… arabesque lines. They are natural because for Mollino divine Nature is the highest reference point we can address, the place where we find the meaning for the word ‘harmonious.’ As a Renaissance architect, Mollino craved to divinely create his forms:

“I can assure you my work as an architect is directed to rid itself of any controversial or intellectualistic postulation to make sure that the architectural form springs naturally. Openly ‘Jaillir.’ This shift from the closed form (functionalism—which I intend as a poetic result, not as a ground for controversy) toward an open form is something I can only carry out with great care, for I do not want to fall into the trap of decorativeness—a sort of ‘Neo-Liberty,’[^] one might say. In other words, the shift (and here I feel I am almost alone in this direction) must take place ‘necessarily’ and naturally. So I will be nature—not nature in the literal sense, but in the sense of my spirit—and I will follow my own interior rules to originate forms in absolute naturalness, and thus freedom.”[^]

LIST OF WORKS

The list includes all the projects by Carlo Mollino which were realized or published, as well as the competitions he took part in. It does not include minor projects that remained secluded in the drawers of his office, never realized nor published.

A reference point for this list of works is the book in Italian edited by Fulvio Irace, Carlo Mollino 1905–1973, Electa, 1989. A catalogue raisonnée exclusively regarding Mollino’s furniture has also been published: Fulvio Ferrari and Napoleone Ferrari, The Furniture of Carlo Mollino, Phaidon, 2006.

1930

- Architettura rustica nell’alta Valle d’Aosta (Country Architecture in the Upper Aosta Valley) – survey drawings[^]

1931

- Edificio per negozi e uffici (shop and office building) – Turin, published[^]

1932

- Villa in montagna (mountain villa) – published[^]

1933

- Sede Federazione Agricoltori, 1933-35 (offices of the Farmers’ Federation) – Cuneo, extant

- Vita di Oberon (The Life of Oberon) – novel[^]

1934

- L’Amante del Duca, 1934-36 (The Duke’s Lover) – novel[^]

- Stand for Marus (stand design for an exhibition) - Turin[^]

- Casa del Fascio (local Fascist Party Headquarters), collaboration with Eugenio Mollino – Voghera, extant[^]

1935

- Tè Numero 2 (art installation for an exhibition) with Italo Cremona – Turin[^]

1936

- Casa Miller (Mollino’s apartment) – Turin, demolished

- Casa nella pineta del Forte (House in the Pine Forest, for Mino Maccari) – Forte dei Marmi, published[^]

1937

- Casa d’Errico (d'Errico apartment) – Turin, demolished

- ‘Casa degli sport’ shop and Luciana and Leo Gasperl apartment – Cervinia, demolished

- Ampliamento albergo Stazione Museroche (hotel Extension at Museroche Cable Car Station) – Cervinia, in ruin[^]

- Società Ippica Torinese, 1937-40 (Horse Riding Club of Turin) – Turin, demolished

1939

- Casa Devalle I (Devalle apartment) – Turin, demolished

1940

- Casa Devalle II (Devalle apartment) – Turin, demolished

- Shelf and coat hanger for Italo Cremona – Turin

1942

- Radio for Mr Bressi – Turin

- Camera da letto per una cascina in risaia (bedroom design) – Piedmont, published

- Casa in collina (House on the Hill) – Turin, published

- Villa Damonte – Capri, published[^]

1943

- Concorso Garzanti (competition for furniture designs) – published[^]

- Casa sull’altura, 1943-44 (House on the Heights) – South Italy, published

1944

- Furniture for Albonico apartment - Turin

- Casa Ada and Cesare Minola, 1944-1946 (Minola apartment) – Turin, demolished

1945

- Casa Franca and Guglielmo Minola, 1945-1946 (Minola apartment) – Turin, demolished

- Monumento ai caduti per la libertà, 1945-47 (monument to the fallen) – Turin, extant

- Casa del Sole, 1945-1954 (apartment building) – Cervinia, extant

1946

- Furniture for exhibition at the Pro Cultura Femminile and for M3 (Mollino’s apartment) - Turin

- Stazione del Lago Nero, 1946-47 (sled arrival station) – Sauze d’Oulx, extant

1947

- Furniture for CADMA (exhibition)

- Galleria La Bussola (La Bussola art gallery) – Turin, demolished

- Farmacia Boniscontro (Boniscontro pharmacy) – Turin, demolished

- Centro sportivo in verticale quota 2600 (Vertical Sports Center, altitude 2600 - apartment building) - published

- Architettura, arte e tecnica (Architecture. Art & Technique) with Franco Vadacchino - book

1948

- Casa Capriata and Casa al mare (Truss House and House at the Sea) – published

- Casa a Sanremo (apartment building in Sanremo) – Sanremo, published

- Furnishing for Reale Mutua Assicurazioni (office) – Turin, demolished

- Furniture for Galleria Vigna Nuova (exhibition in an art gallery) – Florence

- Furniture for Agenzia Cavanna (office) – Turin, demolished

1949

- Casa Rama (villa) – Lerici, published

- Casa Orengo (Orengo apartment) – Turin, demolished

- Casa Rivetti (Rivetti apartment) – Turin, demolished

- Il Messaggio dalla Camera Oscura (Message from the Darkroom) - book

1950

- Concorso Vetroflex-Domus (competition Vetroflex-Domus for prefabricated houses) - published

- Auditorium RAI, 1950-52 (auditorium for Italian Television) – Turin, partially extant

- Italy at Work (furniture for exhibition in U.S. museums) - USA

- Furniture for Licitra-Ponti apartment - Milan

- Furniture for Singer & Sons (furniture to be marketed) – New York

- Introduzione al discesismo (Introduction to Downhill Skiing) - book

1951

- Concorso per la Galleria d’arte moderna di Torino (competition for the Gallery of Modern Art) – Turin, published

- Funivia del Fürggen, 1951-52 (cable car arrival station) – Cervinia, published

- Casa Linot, 1951-52 (house) – Bardonecchia, extant

- Albergo ristorante club, 1951-52 (Hotel Restaurant and Club) – Ivrea, published

- Casa per la F.I.S.I., 1951-52 (F.I.S.I. athlete retreat) – Madonna di Campiglio, published

- Casa ad alloggi sul viale Maternità, 1951-53 (Apartment Building on Viale Maternità) – Aosta, extant

- Casa Editrice Lattes (Lattes publishing house office) – Turin, demolished

- Kunsthandvaerkets Forarsudstilling exhibition (chair for exhibition) - Copenhagen

- Furniture for ICS (ICS doctors’ studio) - Turin

1952

- Concorso per il quartiere dipendenti Saint Gobain (competition for Saint-Gobain Employees’ Housing Estate) with Campo and Graffi – Pisa, published

- Casa Cattaneo, 1952-53 (villa) – Agra, extant

- Padiglione Asia (exhibition pavilion) with Campo and Graffi) – Naples, demolished

- Furniture for Acotto and Colonna apartments, 1952-54 – Turin

- Mostra del Ritratto Romano (exhibition design) with Aldo Morbelli - Turin

1953

- Concorso per Palazzo della regione (competition for offices of the Regional Council) with Campo and Graffi – Trento, unbuilt

1954

- Nube d’argento (Silver Cloud, advertising bus) with Campo and Graffi

- Stand Snam-Agip (exhibition design) with Campo and Graffi - Turin

- Officina Fratelli Bosio, 1954-56 (Bosio Brothers Factory) – Castiglione Torinese, extant

1955

- Bisiluro (racing car)

- Furniture for Provera apartment – Turin

1956

- Stand Vis (exhibition design) – Turin

- Villa Scalero (interior design) – Turin, demolished

- Monumento ai caduti, 1956-63 (war memorial) – Fossano, extant

- Concorso per monumento a Camillo Olivetti (competition for monument to Camillo Olivetti) – Ivrea, unbuilt

1957

- Quartiere case I.N.A., 1957-60 (I.N.A. Popular Housing Project) with Bordogna, Campo, Dolza, Graffi and Rosani – Turin, extant

- Casa Fiorini (villa) – Turin, extant

1959

- Concorso-appalto Palazzo del Lavoro, Italia ’61 (competition for Palazzo del Lavoro Exhibition Hall for Italia ’61) with Bordogna and Musmeci – Turin, published

- Sala da ballo Lutrario, 1959-60 (Lutrario ballroom interior design) – Turin, partially extant

- Competition for cutlery for Reed & Burton – Boston, not submitted

- Chair for Mollino’s office at the Faculty of Architecture - Turin

1960

- Casa Mollino, 1960-68 (apartment) – Turin, extant

1962

- Casa Olivero (villa) – La Thuile, extant

- Villa Zaira (interior design) – Turin, demolished

1963

- Baita Taleuc for Garelli family, 1963-65 (Taleuc rascard) – Champoluc, extant

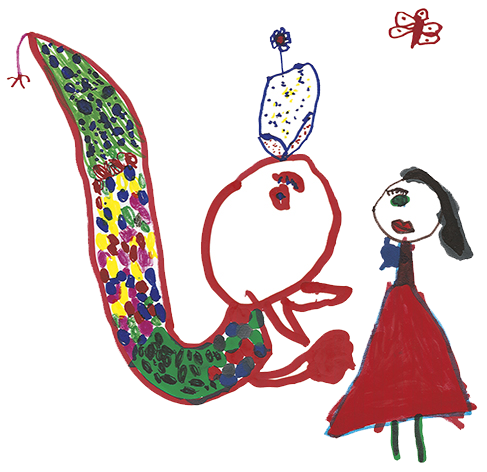

- Drago da passeggio, 1963-64 (‘A strolling dragon’, new year greeting card)

1964

- Camera di Commercio di Torino, 1964-73 (Chamber of commerce of Turin) – Turin, extant

- Concorso per il Teatro Comunale di Cagliari, 1964-65 (competition for Cagliari Theatre) – Cagliari, published

1965

- Teatro Regio di Torino, 1965-73 (Regio Opera House) – Turin, extant

1966

-

Casa Pistoi, 1966-68 (Pistoi apartment) – Turin, partially extant

1973

- Concorso per Palazzo Direzionale ATM (competition for ATM [public transport company] headquarters) – Turin, unbuilt

- Uffici Centrali FIAT di Stupinigi (competition for FIAT headquarters) – Stupinigi, unbuilt

ARTICLES

-

Mollino à rebours

by Paolo Portoghesi, 2015 -

I dioscuri della fantasia

by Italo Cremona, 1978

Museo Casa Mollino

Museo Casa Mollino