by Napoleone Ferrari

Whatever Carlo Mollino did in his life, he always approached it with the mindset of an architect; whether he studied how to ski, take a photograph, design a car or an aerobatic figure, each one of his activities constituted a rigorous and controlled ‘construction’: a project.

Mollino identified himself as an architect, beginning with the protagonists of his autobiographical novels written in his youth, Oberon and Faust,[^] and architecture was his job, the sole activity he continuously pursued throughout his life.

Architecture for Mollino meant Modern Architecture, that is, an original expression of modern times, his own time. Mollino recognized that the Modern Movement embodied authentic modern architecture, but he also believed that for the first time in history, in the 20th century, a dichotomy had been growing between architects and artists on the one side and the public on the other.

The Modern Movement was not recognized by the majority of people but rather existed as a quantitatively marginal phenomenon. For this reason, it was clear to Mollino that the challenge to be faced was not the competition among the different poetics of modernity, the different ‘isms,’ but the fight against both the predominance of merely speculative architecture for financial gain and architecture incapable of meaningful expression, which rendered cities on every continent ugly. In an essay titled “Esiste l’architettura moderna?” (Does Modern Architecture Exist?), Mollino wrote:

“The inspiring condition of the authentic modern architect is to escape to a new, hoped-for world that does not exist yet; one that is not simply a nostalgic reenactment of a lost condition. Therefore, it is the expression of an elite, obliged to remain as such, in more or less open contrast with the majority… Ideal worlds… These exceptions exist on paper, very rarely in reality, only through the demiurgic dreams of those who conceived them, and in the most divergent directions. Perhaps thanks to these dreams, the unconventional and obstinate sect of architects still exists and tries to operate.” [^]

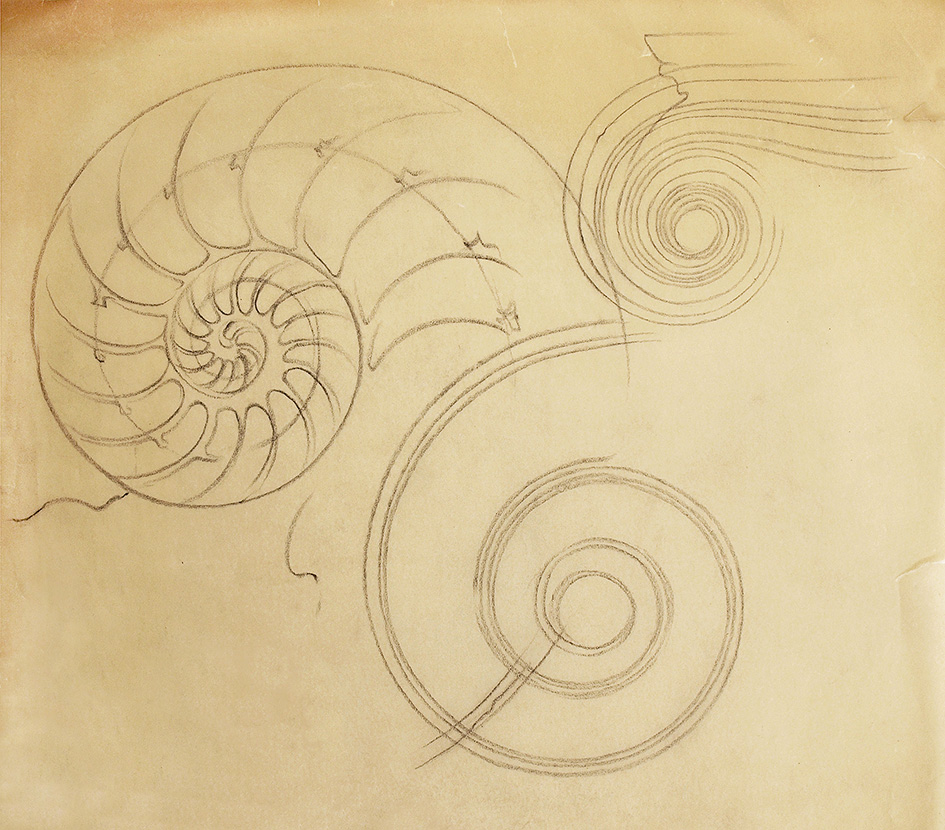

Carlo Mollino, "A shell and Ionic capital volutes," drawing published in Architettura. Arte e Tecnica, 1947. Carlo Mollino Archives, Polytechnic of Turin

Oberon: A manifesto

When Carlo Mollino graduated in 1931, he had already participated in the design and construction of several buildings[^] of diverse typology under the guidance of his engineer father, who at that time was on the eve of building the largest hospital in the city. Work was not lacking, and his father Eugenio vigorously complained about Carlo’s inadequate presence in the office,[^] who, in his turn, was absorbed in other activities.

In this context of remunerative and prestigious construction activity, Mollino was enjoying writing a novel, “Vita di Oberon” (The Life of Oberon),[^] whose protagonist was the architect Oberon. Giuseppe Pagano, director of Casabella, the most authoritative Italian periodical on modern architecture, welcomed its publication in the summer of 1933.

Oberon never existed except as a character personifying Mollino’s life program, which could be synthesized using Oberon’s own words as “his pragmatic way of ‘living poetry.’”[^]

Accustomed to the practice of an engineering studio, Mollino was completely at ease with the technical aspects of building and rather attracted by the ‘lyrical’ ones (to use a term in vogue in Italy in the 1930s to define the eminently artistic aspects of architecture).

Mollino was thus in the position of demythologizing the emphasis on functional and technological elements typical of the ‘heroic era’ of the Modern Movement and ready to create his own new mythology of which Oberon was the first chapter in a lifelong-lasting work of construction:

“Oberon passed through the human condition and endured its hardships and death, while always working strenuously in favor of the group that exalts him, and continuing to act from the tomb. The founders of colonies and the restorers of cities fall within the category of heroes.

Hesiod already placed the hero midway between gods and men, his relics, true and fictitious, forming the radiating center of his power and an effective guarantee for the group possessing them. In Maori mythology, he is completed with the attributes of the ‘creator genius.’ This demiurgical nature of Oberon the architect was expressed by his serenity, the way he acted within the passions of people and things with self-assured detachment, and the way he accepted and employed those passions according to the laws also in the struggle imposed by God, a struggle that is nature’s harmony.”[^]

Through a literary-metaphorical depiction, Mollino-Oberon defined a philosophical position recognizing Nature and History as the environments in which architects operate. But what really puzzles us about these words is the narrative created by Mollino. Why would a modern architect speak in these terms, in 1933?

Here lies a crucial aspect of Mollino’s work and personality, one of the most difficult to make clear. While it is not really possible to rationalize it, the closest we can get is to simply say that Mollino was just like a writer, who finds pleasure and the reason for his being in creating and telling stories.

Yet the unexpected outcome was that if Mollino initially used words to tell his tales, as one would expect, he then stopped writing and went on to create a narration through his architectural work. This is the reason why one of his pieces of furniture may evoke a prehistoric skeleton or one of his buildings might suggest a flying device… Mollino constantly tried to sublimate the functional-structural components of his designs into an expressive narrative.

So Oberon represents a manifesto in a double sense: on the one hand, it was a program for Mollino’s life; on the other, it coherently embodied his message in a playful way and through a creative narration.

Mollino purposefully eschewed the distinctive manner of avant-garde architecture and art manifestoes, which were in the prosaic form of programmatic points and prescriptions intended to indicate a path. In so doing he established his original position in modern architecture history without ever intending to establish a ‘Mollino school.’

Themes & Variations

On looking at all Mollino’s architectural projects and buildings, it is not immediately evident that a single author lies behind them. Depending on the context and building typology he could come up with quite different solutions and forms. It is sufficient to compare the first three buildings he designed (the Farmers’ Federation, the Horse Riding Club, the Lago Nero Sled Station) to note significantly different approaches.

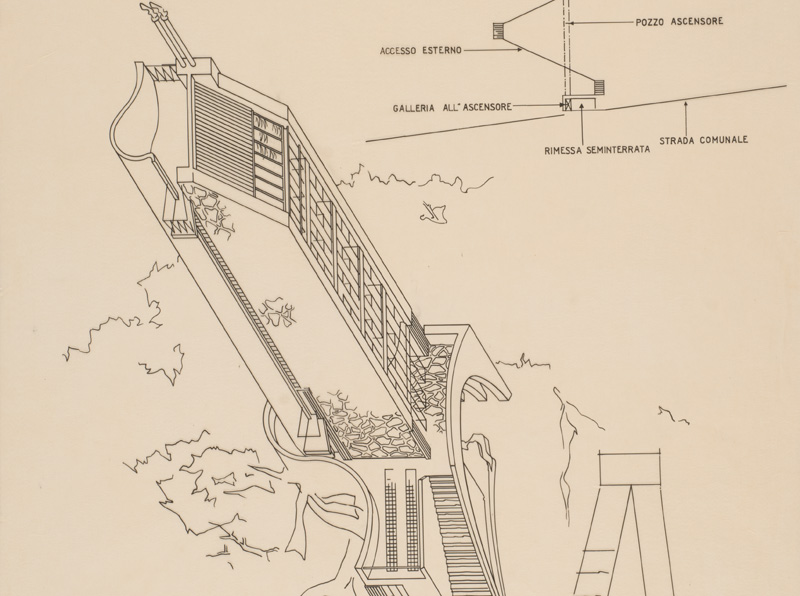

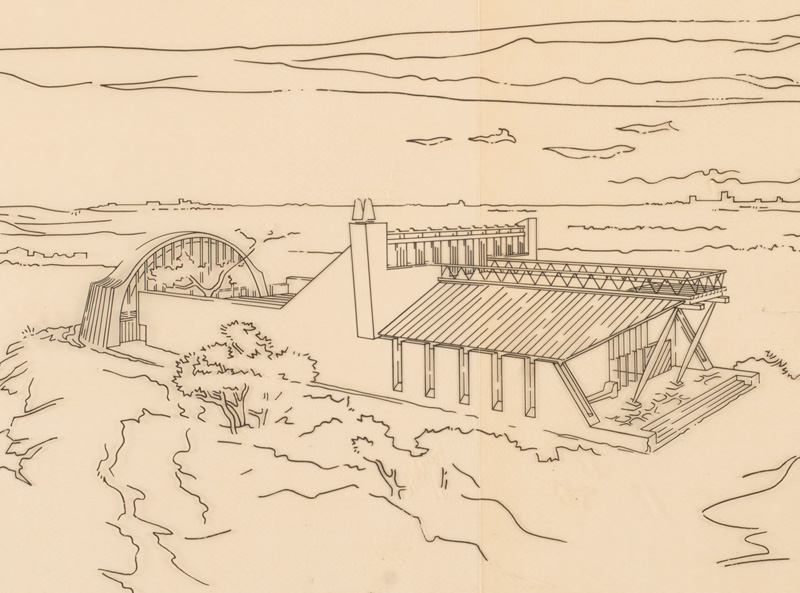

Similarly it is intriguing to follow the evolution of one of his projects from its first design to its final realization, which often turns out to be significantly different (see the Lago Nero drawings here beside).

On the other hand, sometimes it is possible to follow the same single architectural idea repeating and evolving over time in different variants in order to adapt to different locations and functions until it finds its final building stage (one of the most interesting examples in this sense is the project of Casa Cattaneo).

That said, it is in any case possible to delineate a number of conceptual themes characteristically belonging to Mollino’s oeuvre and this has been done in the Works section. In a more empirical way, a number of personal traits in his nature can also be traced that shape a distinctive Mollino taste.

Among these traits we find, for example, a sensitivity more akin to the female than to the male character: Mollino was interested in qualities such as elegance, mystery, sensuality, and emotions; his mind worked in a holistic way, which neuroscience recognizes as being more distinguishing of women while men are more inclined toward a determined logical-rational sensitivity. Women host life in their bodies, they welcome and generate relationships, which Mollino did by contaminating different worlds, constantly trying to unify and connect rather than to disrupt. Without forgetting that it is not by chance that ‘the feminine’ was an essential component of Surrealist culture, which profoundly influenced Mollino.

Another typical feature of his architecture is the quest for volumetric movement, aerial suspension, and overhanging structures, a search for lightness and dynamic tension.

Related to this is a constant search for depth of surfaces and volumes. Mollino achieved such depth with different strategies: the treatment of surfaces with an extended use of textures made of rough materials, different finishes, and colors; he systematically placed the surfaces of volumes at different levels in space with protrusions and recesses and he made use of curved surfaces.

The kind of depth he made use of was also conceptual, in the sense that his projects brought together a quantity of cultural, literary, psychological, functional, structural, and evocative references. Mollino preferred complexity[^] over simplicity and clarity, which led to his works being three-dimensional,[^] pertaining to the complexity of life and often not easy to disclose.

It must also be noted that one of his favorite settings for his buildings were the mountains, an environment congenial to his feeling for nature and a vivid scenario.

Finally, it should be emphasized that in the context of architecture Mollino did not allow himself the same exuberance and formal freedom used for interiors and furniture design, eminently private spaces; instead, he recognized architecture as a specific arena in which a more controlled and austere language should be used.

List of buildings

The Carlo Mollino Archives at the Polytechnic of Turin contain 123 different architectural projects designed by Mollino between 1930 and 1973. Only 14 projects were actually built. Here below is a list of the most significant projects, both built and unbuilt.

-

In March 1933, Carlo Mollino together with the engineer Vittorio Baudi di Selve won the competition for the construction of the new offices of the Farmers' Federation in Cuneo. The first building designed by Mollino is visibly influenced by the architecture of Erich Mendelsohn, in whose studio Mollino had briefly worked two years earlier, but also combines elements of Italian Second Futurist architecture and of Metaphysical art.

https://cuneofotografie.blogspot.com/2014/01/edificio-di-carlo-mollino-sede-della.html -

In charge of designing the seat of the Horse Riding Club of Turin with the support of the engineer Vittorio Baudi di Selve, Carlo Mollino innovatively introduces elements borrowed from Surrealism and Metaphysical art in the horizon of the Modern Movement. He effectively merged functional architecture with expressive themes designing his first masterpiece and an innovative design in the history of architecture.

https://casabellaweb.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/CB-157.pdf

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FPuOy7Df6jY

https://rudygodinez.tumblr.com/post/70080577269/carlo-mollino-societ-ippica-torinese-1937-1940 -

Giuseppe Pagano invited a group of Italian architects to design their own 'ideal house' for the magazine Domus; Carlo Mollino designed a seven-story tower to be erected on the Turin hillside, containing only one room per floor in homage to the 'Fetta di polenta', the house built by Alessandro Antonelli in Turin. The project was published in the issue of February 1942.

-

Described by Carlo Mollino as a pavilion, a tent that Assyrian kings used to take with them on hunting sorties, the villa is perched on a hill in southern Italy, its structure inspired by the Roman Domus, closed in around an internal courtyard. The project was not built, and Gio Ponti published it in Stile, April 1944, together with an evocative letter from Mollino himself describing the genesis of the project.

-

Carlo Mollino and the sculptor Umberto Mastroianni won the competition issued by the city of Turin for a monument to be erected in the town’s cemetery in memory of the partisans fallen during WWII.

The two conceived a figurative monument accessible to the general public with a direct symbolism.

-

The building was commissioned by engineer Dino Lora Totino, president of the Cervino cableways company, to implement the accommodation facilities of Cervinia. Carlo Mollino transforms the geometry of the facades of the traditional wooden Walser alpine houses, of which he was a connoisseur, into a reinforced concrete orthogonal modernist structure unbalanced at the top by a small villa hovering like an eagle's nest.

http://www.adartepublishing.com/en/catalogo.asp?libro=1184667462

-

Carlo Mollino creates a sculptural building by intersecting a double-pitched roof on the north side with a single-pitched roof on the south side. On the structure composed of five reinforced concrete Vierendeel beams he inserts on the upper floors an infill of logs. The building, commissioned by Piero Dusio, owner of Cisitalia car brand, was the arrival point of a sled-lift system, it contained a bar-restaurant and served as a refuge.

https://www.atlantearchitetture.beniculturali.it/en/slittovia-al-lago-nero/

http://www.ideabooks.com/shop/carlo-mollino/ -

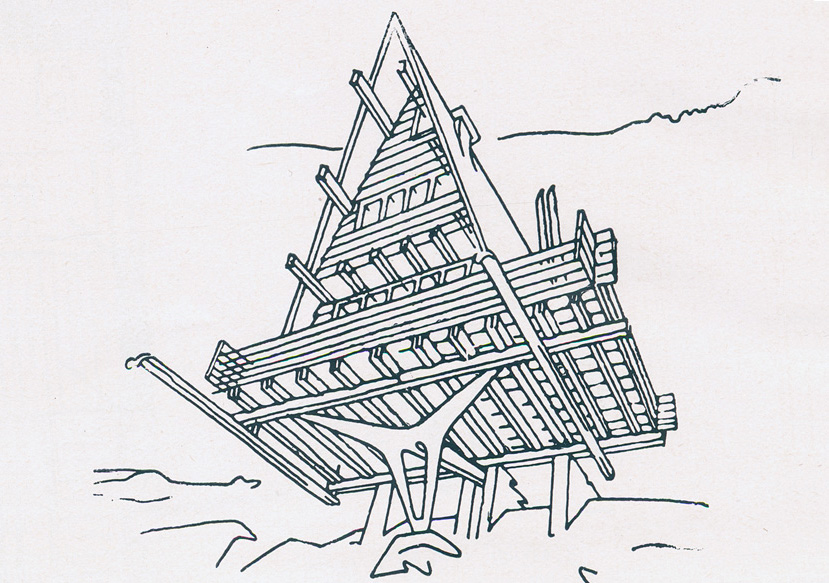

This small weekend house for skiers was conceived by Carlo Mollino as a simple shape that could be prefabricated using minimal wooden elements. It was an insulated box to be mounted on any mountain terrain suspended on different kind of structures.

A re-interpretation of the truss house was elaborated by architect Guido Callegari in 2008.

-

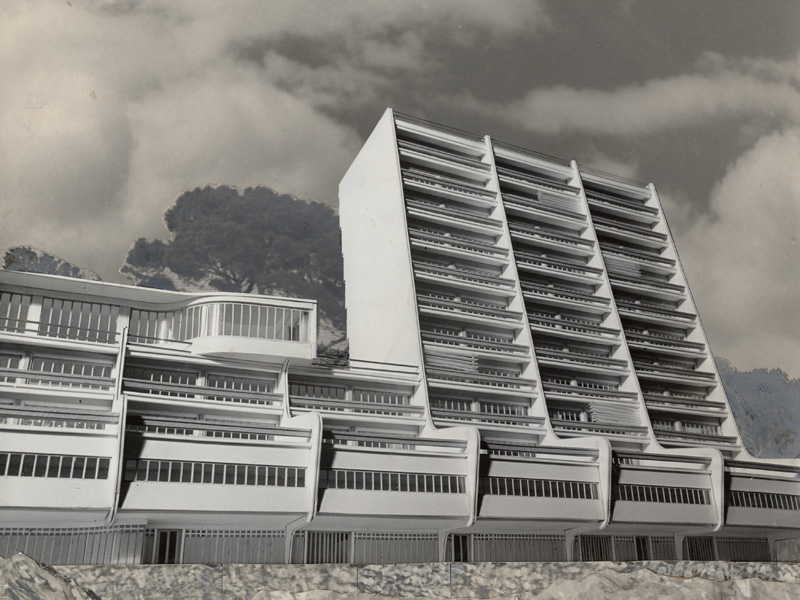

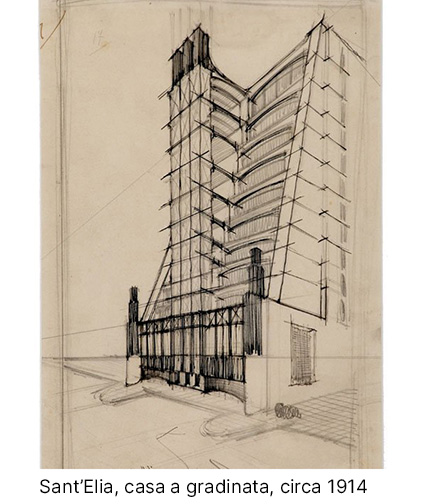

Referencing Sant’Elia[^] architecture, the apartment block to be built on the Ligurian coast was unusually leaning back and made use of typical Carlo Mollino’s geometrical lines and asymmetrical composition. For its interiors Mollino conceived exquisite designs which he later used for other projects since the building was never built. The project was conducted in collaboration with architect Mario Roggero.

-

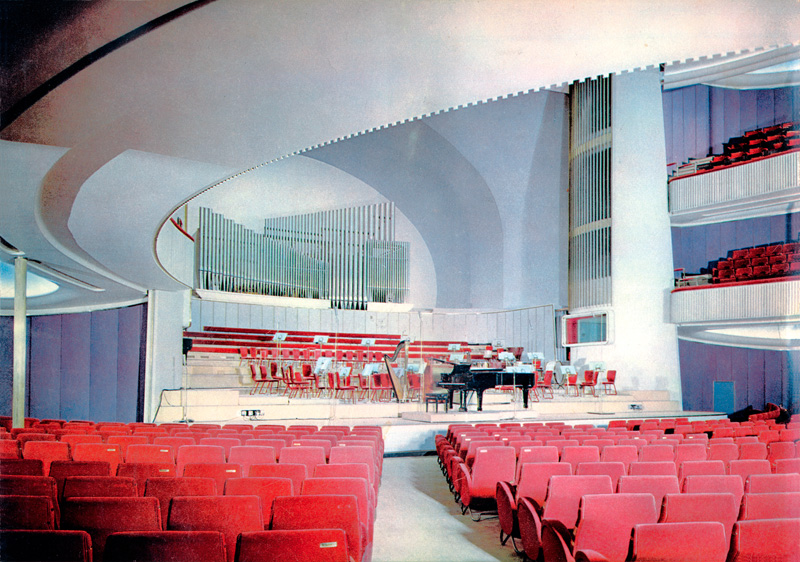

Carlo Mollino redesigned only the interior of the concert hall inside the 19th century structure of the pre-existing Teatro Vittorio Emanuele. He elegantly transformed the rigid neo-classical structure into a fluent shell-shaped plan updating the auditorium to modern technologies for tv and radio broadcastings. In 2005, the stage part and focal point of the auditorium has been completely erased.

-

The Aosta Valley Region commissioned Carlo Mollino a social-housing project. He played on pre-war schemes of Italian Rationalism to design a horizontal volume highlighted by the use of many different and colorful materials and finishes reflecting Italian post-war cheerful spirit.

-

The small villa for the Cattaneo family sits like a resting animal, yet ready to jump, on the hillside overlooking the Lake Maggiore. Carlo Mollino designed with great care all its details and conceived an unusual structure concealed in the roof to sustain the large span of its central part. Originally the house was camouflaged using green and yellow enameled roof tiles.

-

1959 Concorso-appalto Palazzo del Lavoro, Italia '61

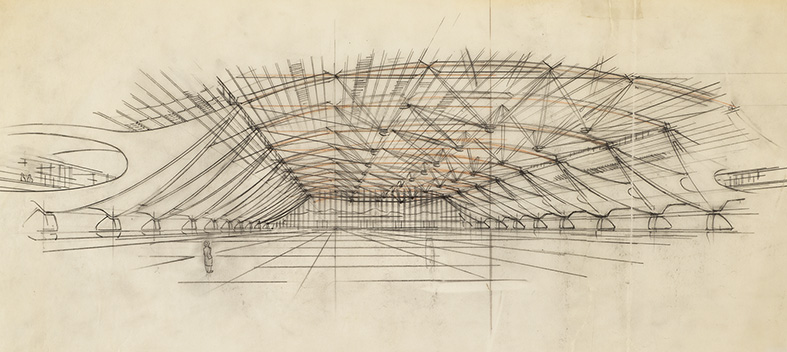

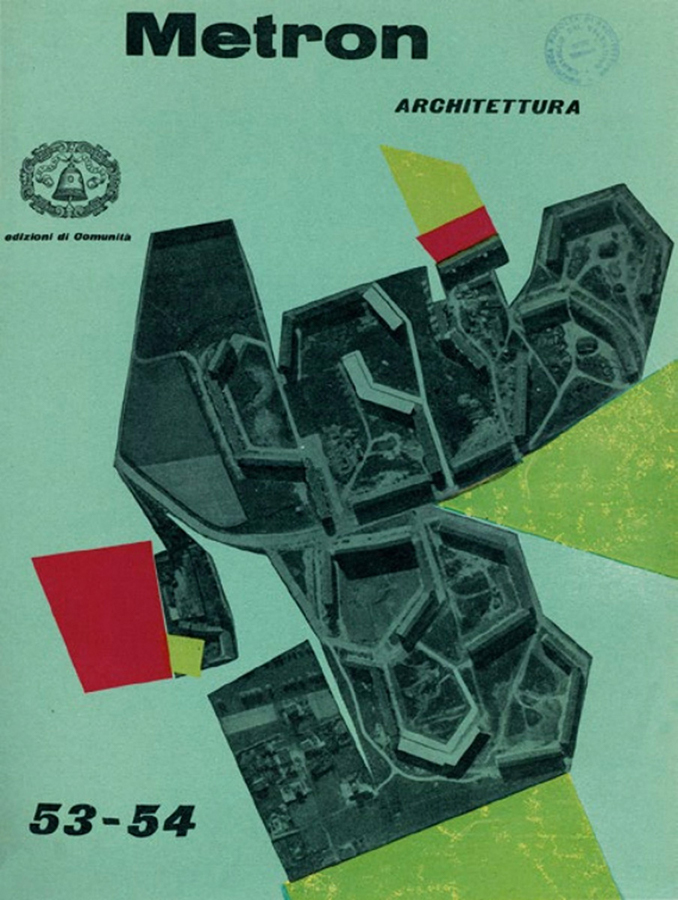

Palazzo del Lavoro Exhibition Hall for Italia ’61, Competition

TurinThis project ignited Mollino's interest in large concrete structures that marked the last part of his work. Carlo Mollino with architect Carlo Bordogna and engineer Sergio Musmeci took part to the competition issued by the city of Turin for an exhibition hall to be built in occasion of the celebrations for the unification of Italy. They presented three different technical options to cover the large span required. The project was assigned to Pierluigi Nervi who placed several columns inside the building not compelling with the free span required.

-

Clotilde and Felice Garelli acquired the rascard Taleuc (1664) with the intention to transform it into their mountain weekend house. The building was dismounted from its original location and brought in nearby Champoluc where Carlo Mollino modified the building turning a former storage into a home. Mollino did a rigorously philological work with the only addition of a modernist concrete staircase on the outside.

https://www.marcellomariana.it/rascard-garelli/

https://www.electa.it/en/product/carlo-mollino-larte-di-costruire-in-montagna/ -

The block of the offices is suspended from the roof by means of tie rods arranged along the four facades, and in turn the roof is supported by a central reinforced concrete body. This special structure, one of the first in the world to be built, allowed large functional interior spaces free of columns.

Carlo Mollino won the competition for the construction of the Chamber of Commerce together with the engineer Antonio Migliasso (later substituted by Felice Bertone) and the architects Alberto Galardi and Carlo Graffi.

http://www.adartepublishing.com/en/catalogo.asp?libro=1278589713

-

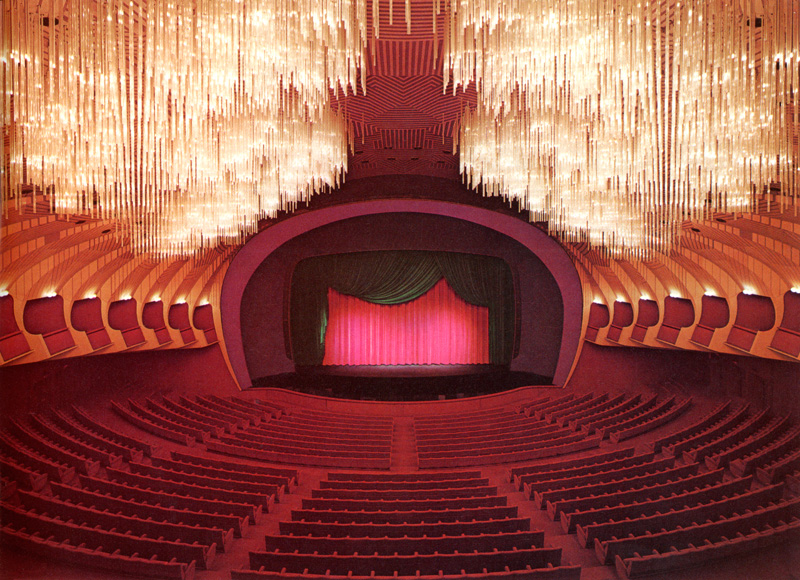

One of Carlo Mollino's masterpieces, the Teatro Regio is essentially composed of a foyer inspired by Piranesi's architectural visions of the “Carceri”: a fascinating open space in reinforced concrete; the auditorium: a large egg that envelopes the audience and the stage in a completely curved space; the technical part of the stage: still one of the most modern and functional in Europe. Together with Mollino, the project was supervised by the engineers Sergio Musmeci, Marcello Zavelani Rossi, Felice Bertone and the architect Carlo Graffi.

https://www.darioflaccovio.it/architettura-e-tecnica/24-teatro-regio-torino-storia.html

Museo Casa Mollino

Museo Casa Mollino