by Napoleone Ferrari

Carlo Mollino was a sportsman, his person presenting “a dry and petite stature, a hollowed-out face and above all a snappy style, taken from the world of the circus, à la Cocteau, a bit like Charlot.”[^] This is how professor Roberto Gabetti, Mollino’s assistant at the Polytechnic of Turin in the 1960s, has remembered him.

Mollino belonged to a generation who grew up in Italy in the 1910s and 1920s under the influence of Tommaso Marinetti’s Futurism, under the myth of ‘action’: sport and the machine.

Browsing through the photos of the young Mollino we find him skiing, climbing in the mountains among rocks and in snow; we see his father on a sidecar, or both of them climbing about on planes; and we must not forget that mechanical industry was the beating heart of Turin’s economy.

Before and after becoming an architect and later a professor, Mollino zealously cultivated his sporting verve. The “snappy style” of his person was the same we recognize in his buildings and furniture accomplishments.

Mollino was a ski instructor, gentleman driver, and aerobatic pilot. He never became a professional sportsman, his profession was another, yet he tried his hand in each of these disciplines, distinguishing himself and, above all, tackling their technical and theoretical aspects, leaving his personal contribution to these sports.

Carlo Mollino, 1920s

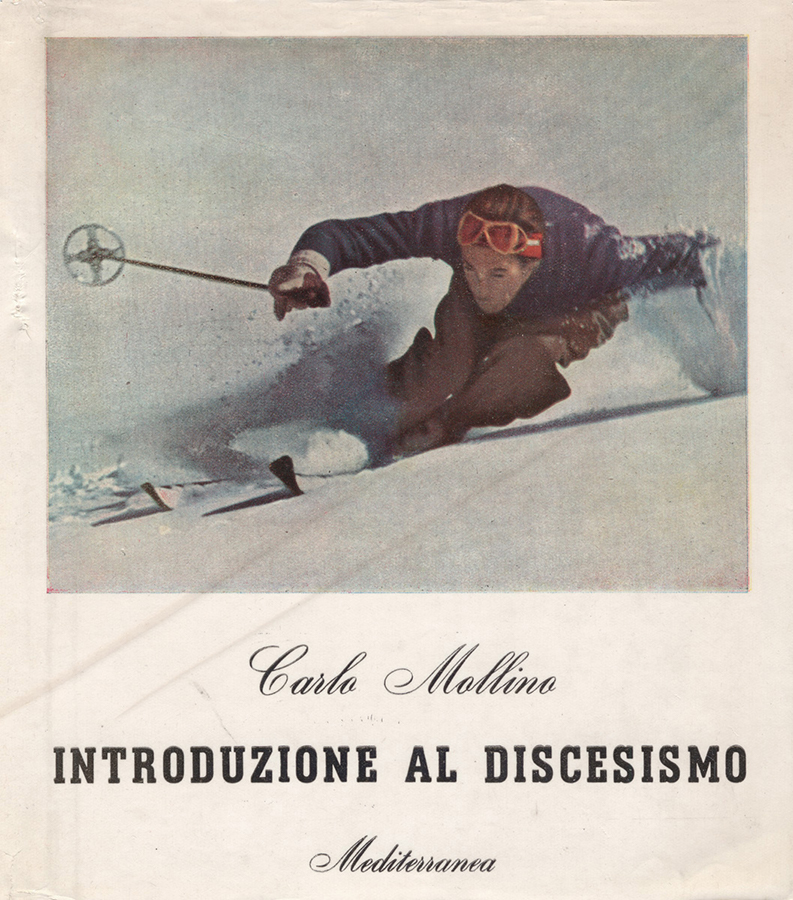

SKIING

In the winter of 1934[^] his father, Eugenio, took Carlo Mollino skiing for the first time, when he was 61 years old and Carlo was almost 29. Skiing turned out to be a veritable passion for Carlo, powerfully reinforced in 1936[^] through his friendship with the Austrian skier Leo Gasperl, trainer and founder of the Italian national alpine skiing team since 1932. Mollino soon began to photograph Gasperl and technical discussions on skiing arose among the two since Gasperl was preparing a manual on the theme.

In that pioneering era, all was in rapid evolution: skis, downhill techniques, ski lifts. Eugenio Mollino, a methodical engineer, studied and patented a new type of binding for boots and skis.

But whereas for Eugenio skiing remained a weekend hobby, Carlo went on to become a ski instructor, in 1942, and during the following winters of the war years he perfected a volume on skiing technique, systematizing the most recent innovations concerning this discipline. In 1943 the acquaintance with the photographer Ermanno Scopinich[^] brought Mollino another stimulating collaboration and in 1945 the material for the book was ready. But the moment was not favorable and he was only able to find a publisher ready to print the 334 pages of Introduzione al discesismo (Introduction to Downhill Skiing)[^] in 1950.

In a magazine review the volume was defined as being “an architectural downhill skiing book,”[^] a description that beautifully renders Mollino’s customary control over his work: the book was written and also designed by him; it was thoroughly illustrated by him with very effective drawings that analytically dissect the movements of skiing; a rich photographic apparatus produced by Mollino himself or otherwise carefully selected implements the technical issues with expressively stylistic ones; the extensive bibliography recorded in the volume reveals Mollino’s careful research among Swiss, French, German, and English volumes and, as always, his desire to investigate first of all the history of skiing and then to synthesize and harmonize different styles, thoughts, and techniques.

BISILURO

Carlo was a decidedly sporty driver, at least according to a witness who swore at the time never again to accept a lift from Mollino.[^] On the other hand, the automotive industry and automobile passion were widespread in Turin, with leading Italian factories such as Lancia and FIAT being based there, as well as a large number of minor brands[^] and workshops along with famous car-body designers such as Pininfarina.

In 1955 the fortunate combination of these elements was distilled in the project of the Bisiluro Da.Mol.Nar[^] car (twin-torpedo DAmonte, MOLlino, NARdi).

Following the success obtained at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1954 by the Turinese pharmacist Mario Damonte with an Osca 1100, Mollino began working to modify[^] the body of the Osca in order to make it more aerodynamic. Enrico Nardi, an experienced pilot, engineer, and car designer, was involved in the project and the three set to in the spring of 1955 to get the Bisiluro ready to take part that very same year in the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

The car was constructed with an aluminum welded tubular frame with its bodywork also in aluminum, being handmade by the CA.MO. workshop of the talented Rocco Motto.

The car, a unique piece now preserved at the Science Museum in Milan, weighed only 450 kg and could reach the speed of 220 Km/h with its 750 cc Giannini engine.

Mollino designed the Bisiluro car starting from its aerodynamic shape then fitting the engine and mechanical parts to it, including the frontal radiator, one of the most interesting innovations, whose outlines follow the body of the car.

On June11 the car ran at Le Mans, performing well in that unfortunate race that saw the biggest accident in automobile history. But at that point the Bisiluro had already ended its race in a ditch, forced there by the air pressure of a much more powerful passing Jaguar.

The Bisiluro was not the only car project by Mollino. In 1953 he designed an advertising bus for the Italian Agip Gas company, together with Franco Campo and Carlo Graffi, and in those same years he also had two scale models made of speed record cars he designed.

AEROBATICS

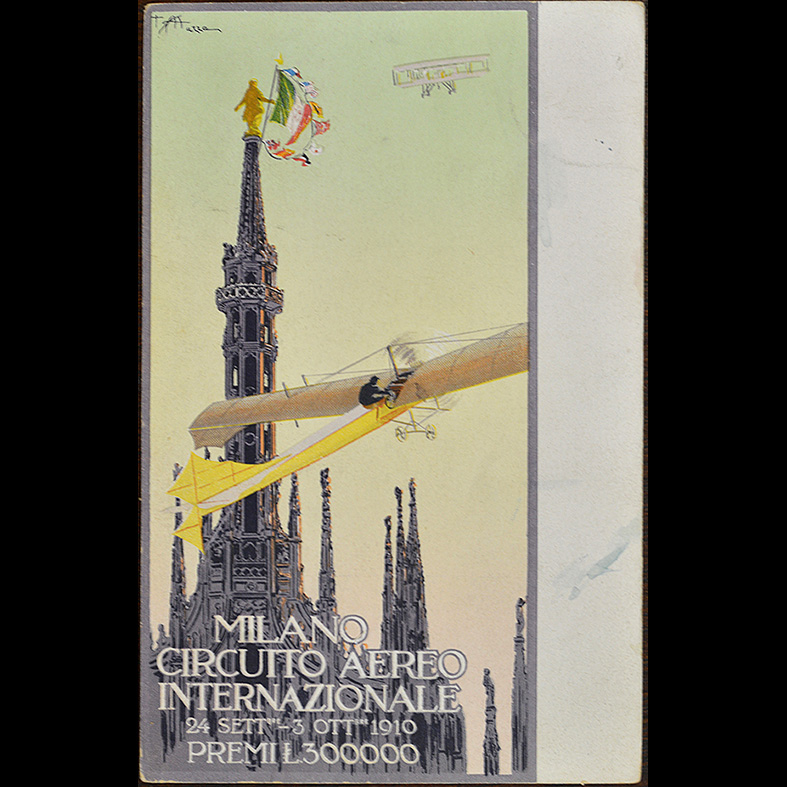

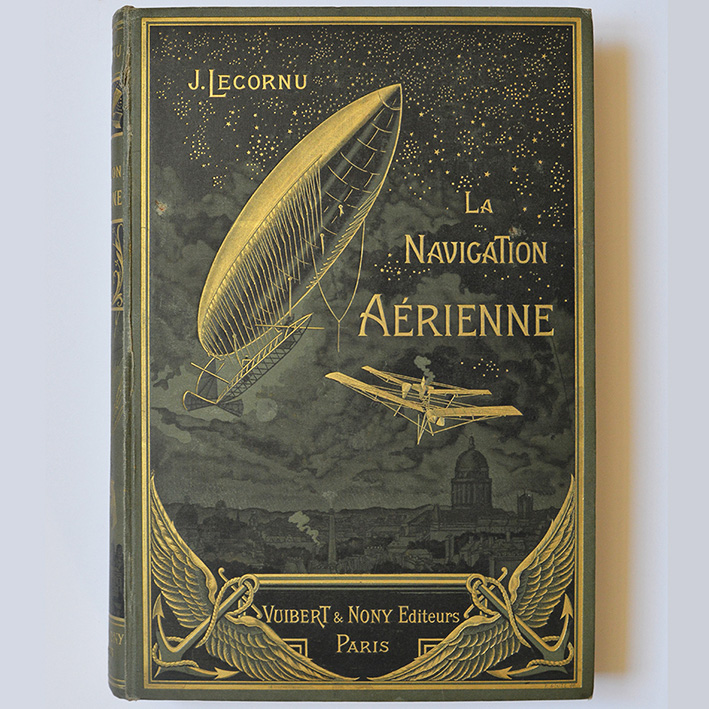

Among his papers Carlo Mollino kept a leaflet of the international air show that was held in Milan at the end of September 1910.[^] Probably his first direct encounter with aviation dates to this time, something that was already familiar to him through the books on hot-air balloons and flying machines[^] that his engineer father kept in his home library. Meanwhile in Turin, in 1909, the first flight of an airplane of entirely Italian construction had taken place.

But Mollino actually began to fly only in the mid-1950s,[^] obtaining a private pilot’s license in 1956 and buying his first plane that same year, a Jodel Aviojeep 1.

For Mollino this was the beginning of a new passion, for aerobatics, since in his own words he naturally belonged to that “certain class of pilots who quite quickly get tired of the simple air cruise.”[^]

The first step in learning how to perform aerobatics, since a school for that feat did not exist, was to find a master, soon identified in the Swiss pilot Albert Ruesch, a world champion of aerobatics. Mollino began to frequent the little airfield of Porrentruy in the Jura mountains and to fly yellow Bücher biplanes. He would later buy for himself a Bücher Jungmann and then a Zlin 226.

By the early 1960s Mollino had become an experienced acrobatic pilot, taking part in national and international air competitions.

In 1962 he designed a plane[^] specifically conceived for performing aerobatics but could not convince a company to produce it. He also worked to set up a school for aerobatics in Turin which, if it had been established, would have been the first in Italy.

In 1964 Mollino became very busy with his architectural work,[^] which forced him to stay away from the airfields that he had previously attended for intense training, sometimes on a daily basis.

Mollino was enthusiastic about aerobatic flight, which consisted of a precisely geometrical exercise performed in the free three-dimension of the sky-space, a practice that well attained his intimate character: “A sport designed to attain harmony in the conscious use of meticulous control.”[^]

In the last years of his life his doctor forbade him to practice aerobatics due to the physical stresses they involve, since he was in a precarious state of health. Carlo, however, never stopped flying until the end in 1973; sadly he was not blessed with a romantic end falling from the sky but, instead, when sitting at work in his office.

Museo Casa Mollino

Museo Casa Mollino