by Napoleone Ferrari

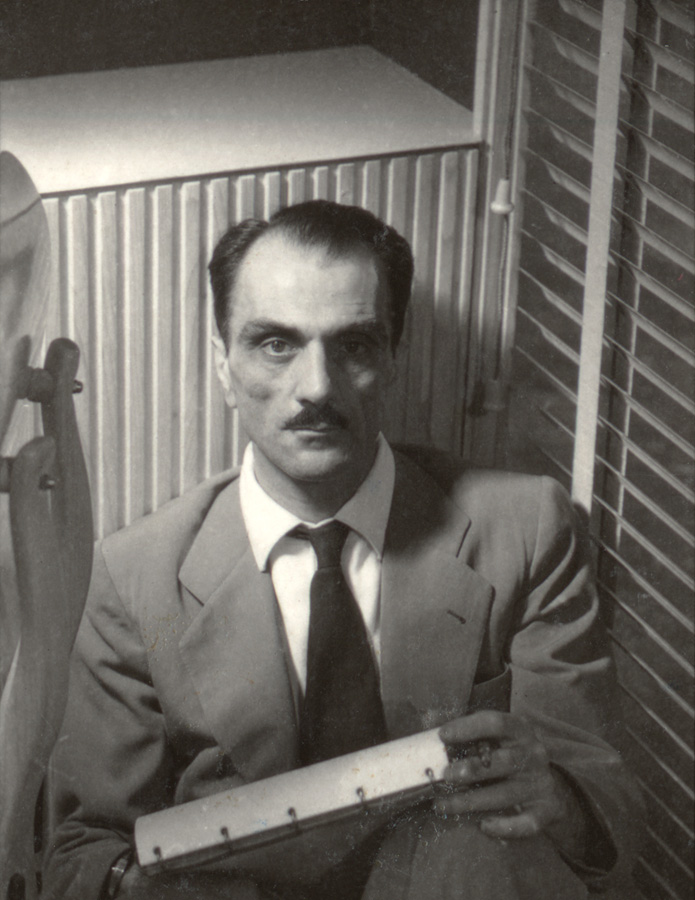

Carlo Mollino (Turin, 1905-73) was an architect who committed equally to art and to technique, embodying the figure of the Italian Renaissance polymath in the context of modernity.

He was a sportsman and a cultured intellectual, besides designing buildings, interiors, and furniture, he was a photographer, a writer, a skier, an aerobatic pilot, and a professor at the Polytechnic of Turin.

In the 1930s he was among the very few architects, internationally speaking, to introduce elements of Surrealist art and culture into the Modern Movement. Free from any rigid ideological position, he went on to define a synthetic form of eclecticism that prefigured the contemporary.

Taking nature as a source for both engineering and harmonious beauty, Mollino was essentially in search of lightness and dynamism, qualities he animatedly infused into his organic architecture and furniture.

An innate pleasure for storytelling colored every aspect of his work:

“Anyone who is not a beast and therefore has the awareness and dignity of a human being, the poorest human being who has never reneged on his own individuality, will feel this need: to be enchanted and to enchant, to express himself.”[^]

1905-1931

Carlo Mollino was born on May 6, 1905, in Turin, one of the most dynamic industrial and cultural centers of Italy. He was the son of the civil engineer Eugenio Mollino (1873-1953) and of Jolanda Testa (1884-1966).

Eugenio, who graduated from the Polytechnic of Turin in 1896, was then becoming one of the most prolific and esteemed engineers in the city. During his career he built over 300 buildings of different typologies, including the largest hospital in town.

Carlo enjoyed a well-to-do childhood in Rivoli,[^] a municipality bordering Turin, in the 19th-century neo-Gothic family villa encompassed by a big park populated with old trees. He grew up surrounded by a number of women: together with his mother, of whom we know little besides that Carlo had great affection for her, his family consisted of three great aunts[^] and a couple of young housekeepers who helped the family. An only son, little Carlo was pampered in this purely feminine environment while his father pursued his professional career with great determination, although not without dedicating attention to his son, pragmatically educating him in modern technologies such as engines, photography, airplanes…

Carlo attended the San Giuseppe College in Turin, from its elementary school to classical studies at its high school. The San Giuseppe, which was run by the Congregation of Christian Brothers, was frequented by the city’s upper middle class and aristocracy; we have valuable testimony of his adolescent period in an article published by Brother Goffredo,[^] his Greek teacher and mentor.

Subsequently Carlo attended a year of engineering at the Polytechnic of Turin after which he managed to move to the newly founded Royal Superior School of Architecture for the year 1925-26. The school was housed in the premises of the Albertina Academy of Fine Arts in Turin, thus allowing the young Carlo to come into contact with an ambient of painters and artists who played a key role in his artistic-literary education, establishing long-lasting friendships and collaborations.[^]

In 1928 he left the army with the rank of corporal after serving only one year in the mountain artillery. In 1929 he attended an art history course at the Sint-Lucas School of Architecture in Ghent (Belgium) for six months and in July 1931 he graduated from the Turin School of Architecture. In the summer of 1931, he spent a few months in Berlin also attending Erich Mendelsohn’s studio.[^]

Already during Mollino’s university years and also after his graduation, his authoritarian engineer father put him to work, promoting Carlo’s collaboration both in the design and the construction supervision of buildings. This apprenticeship was of fundamental importance in Mollino’s acquaintance with the science of construction.

1933-1944

In 1933 Carlo Mollino began to forge his own professional figure, independent of his father’s conventional work. That year he published in Casabella magazine an autobiographical novel, “Vita di Oberon”[^] (The Life of Oberon), and he won his first competition to design and construct an office building.

Eugenio expected that Carlo would one day continue his engineering practice; however, this did not happen, although Carlo worked in that very same studio for the rest of his life, pursuing his personal projects but always assisting his father up until his death in 1953.

Carlo lived all his life at home with his parents, first in Rivoli and then in Turin, although since 1936 onward, when he set up Casa Miller for himself, he kept renting small apartments in town where he could work, thus avoiding his father’s control, and where he could meet his friends.

The outbreak of war found him busy finishing the Horse Riding Club of Turin; he escaped enlistment thanks to his employment as a technician at the Televel aeronautical construction company belonging to his friend engineer Ettore Caretta. By the way, it should be noted that Mollino never joined any political party, before or after the war, and not even in his writings or private letters is there any mention of political or religious ideologies.

Evacuated from Turin because of the bombings and returned to live in the family villa in Rivoli, during the war years Mollino devoted himself mainly to writing his two books on photography and skiing, which were then published in the immediate post-war period, while in 1942 he got the diploma of ski instructor.

1945-1973

With the end of the war an intense, hardworking period began for Carlo Mollino that saw him engaged with architecture, interior design, and in writing a number of essays and books. In 1949 he began teaching at the Faculty of Architecture in Turin, becoming full professor in 1953. Between 1948-55 he lived his most important love story with the sculptress Carmelina Piccolis.

In December 1953 his father Eugenio passed away and a period of personal crisis began for Carlo who, for about five years, almost completely abandoned his work as an architect. In those years, he designed the Bisiluro racing car, 1955, which ran at the 24 Hours of Le Mans; in 1956 he got his airplane pilot’s license, and also that year he began a photographic project on nudes.

The year 1959 saw his return to architecture with the competition for Italia ‘61 and the design for the Lutrario Ballroom, thus opening a new period of great commitment to work throughout the 1960s. He built the Chamber of Commerce and the Regio Opera House, both in Turin; he continued to teach; he dedicated himself intensely to aerobatic flight and competitions; he spent countless nights taking hundreds of Polaroid photos; and he created for his own use the interiors of the apartment in Via Napione.

In 1966 his mother passed away. As for Mollino himself, in the early afternoon of August 27, 1973, while he was alone at work in his studio, he was seized by a respiratory crisis[^] that resulted in a fatal heart attack.

Museo Casa Mollino

Museo Casa Mollino