by Napoleone Ferrari

Carlo Mollino matured a love for drawing since he was a child, later developing his exceptional ability of drawing with either his right or left hand or drawing using both hands simultaneously, also moving them independently like a pianist. His architectural drawings are very effective, realistically rendering perspectives and three-dimensional space.

In his autobiographical novel Mollino described his ability to represent reality: “I never drew to scale. I did the drawing by imagining it in space as I ‘saw’ the construction. I moved around it, went into it, and moved toward all its details.”[^] Such a description implies he had a vivid imagination, a sort of ‘photographic viewpoint,’ as if he had a camera built in his mind.

It is true that confidence with a camera came about very soon thanks to his father, an engineer who used photography early on to document his work and who had set up a darkroom at home.[^] A photo of circa 1910 shows a proud little Carlo, camera in hand.

While never painting nor using his extraordinary talent for drawing in making art, limiting it to his profession as architect, Mollino deliberately chose photography as an eminently modern[^] form of expression.

Beginning in the 1930s and almost continuously during his lifetime he made a wide-ranging use of photography: as an architect, as an artist, in a technical and documentary way, directing other photographers, printing, retouching images, producing photomontages.

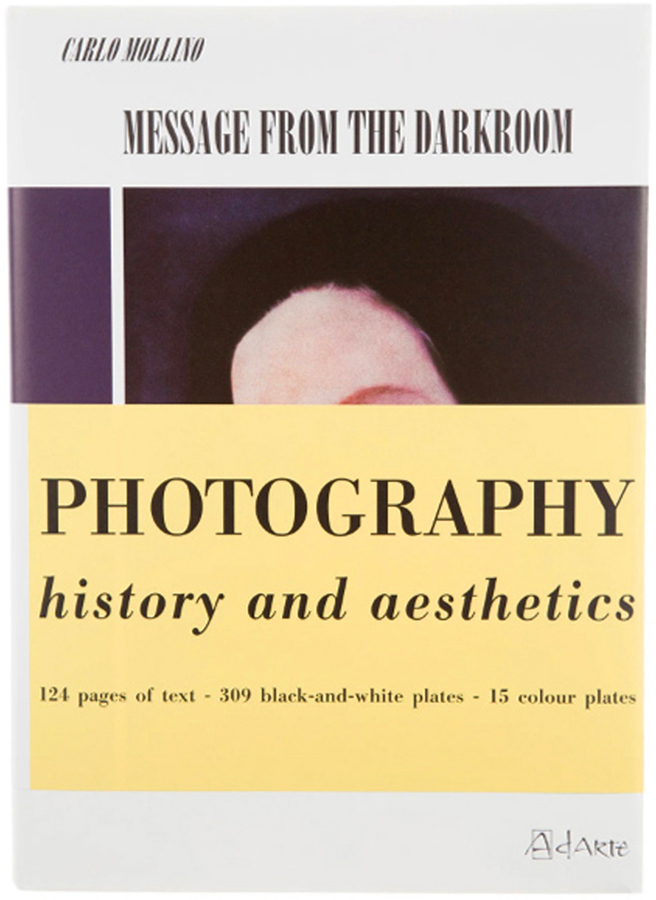

In 1949 Mollino published a significant book on the history and critique of photography, Il Messaggio dalla Camera Oscura (Message from the Darkroom), whose concluding words well explain his love for photography:

“On fragile sheets, between one pulping and another of today’s ephemeral life of paper, I encounter photographs, concrete poetry that ferries me into the domain of the ineffable as much as a consecrated painting or other canonical art form; these photographs being ‘personal documents’ or fantasies of an impossible daily life.”[^]

Carlo Mollino holding a camera among his family women in the Rivoli villa garden. Photo Eugenio Mollino, circa 1910

MESSAGE FROM THE DARKROOM

In considering photography Mollino did not need to spend time on the age-old debate about whether photography could be considered art or not, his position was firm:

“Any moment of resourceful human action may bring the opportunity to create a taste for a new and unexpected language and yet another muse. The other nine muses, traditional and original, may watch the glass eye and black box suspected of too many gratuitous prodigies with hostility from Helicon, but Venus smiles and the muses’ mother Mnemosyne, goddess of memory, also smiles at her latest child: the ways of poetry are infinite.”[^]

In the 444 large-format pages of Il Messaggio dalla Camera Oscura (Message from the Darkroom),[^] which by the way is the first systematic book on photography published in Italy, Mollino introduced the topic with the history of photography; then he analyzed its technique both in an empirical manner and by addressing its central conceptual themes. Some titles of the book’s chapters guide us to his understanding of photography: “Beauty is not art, but an ‘opportunity’ for art,” “The apparent mechanical objectivity of the photographic lens,” “The technical photographic means of aesthetically transfiguring nature.”

The book was completed by a selection of approximately 300 images from all over the world illustrating a wide range of subjects and photographic genres (propaganda, fashion, sport, documentary...). As usual Mollino was not interested in establishing a specific use of photography or any poetics but rather in achieving a comprehensive point of view in which “All is permitted,” to use another title from his book.

What mattered mostly to Mollino was the message created in the darkroom of human minds and then deposited on thin layers of paper by means of silver salts.

B&W PHOTOGRAPHY, 1934-1948

Carlo Mollino signed his first photo in 1934, an image transformed into an illustration[^] for his novel “L’amante del Duca” (The Duke’s Lover). Shortly afterwards, Gio Ponti gave him the first public recognition, publishing one of his images as a cover of Domus in April 1937.

Once his studio-apartment Casa Miller was ready, in 1936, Mollino began to use it as a set for his B&W female portraits.[^] “Fairy tales for grown-ups” is the title of a photo that could be emblematic of this body of work made up of about 40 signed photos taken up until 1942,[^] in which Mollino’s constant desire to transfigure reality into a literary dream emerges.[^]

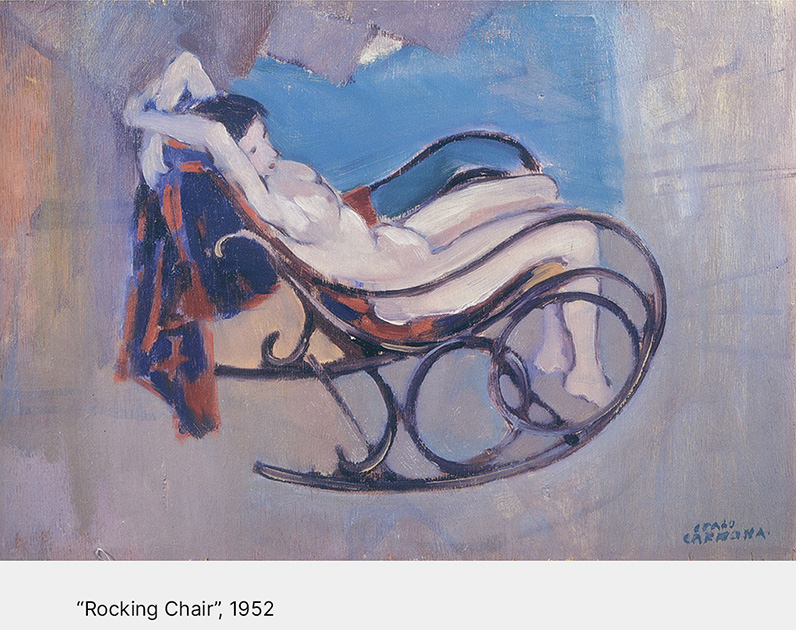

Images were highly controlled and prepared with a careful choice of objects, clothes, and hairstyles, in the manner of the fashion shoots of such vanguard photographers as Man Ray or Erwin Blumenfeld. One can sense in Mollino’s images a strong affinity with the Pre-Raphaelite model of woman, or of muse (an affinity shared with Mollino’s best friend and painter Italo Cremona[^]), enhanced by the inclusion of symbolic, architectural, and Surrealist elements often hovering in the compositions.

In 1939 Mollino joined Turin’s photographic society and subsequently took part in public photographic exhibitions in Turin and Italy. This was the main stage for his photos, while a few were published in photographic magazines, and in 1945 Ermanno Scopinich published a tiny book with 19 of his photos.[^]

Another, larger body of B&W photographs portrays Mollino’s own architecture and interior designs, making him twice author: as architect, and as photographer. These photos are particularly interesting since they offer an interpretative key provided by their own author, especially when Mollino went on perfecting his architectural work with forms of photographic manipulation, such as retouching, special frame cuts, photomontages.

These techniques deliver a strong expressive charge actively contributing to bringing Mollino’s Surrealist imaginary into the frame of the Modern Movement; in this sense these photographs stand as an innovative work in both photography and architecture history.

In the early 1940s, Mollino dropped this work, leaving to professional photographers the duty of documenting his architecture for publication in magazines, although he always carefully controlled and selected the production of the images.

SKI PHOTOS, 1937-1945

The encounter with the Austrian skier Leo Gasperl in the mid-1930s offered Carlo Mollino a new photographic option: to look at skiing as an artistic performance, a happening that the camera could fix in a significant moment.

After setting the world speed record in 1932 in St. Moritz, Gasperl became the first coach of the Italian national alpine ski team that same year. Gasperl mastered a perfect technique and enchanted people with his elegance. Mollino found in Leo the perfect blending of art and technique and made him his favorite model; at the same time, photography, of which were both passionate, cemented their friendship.

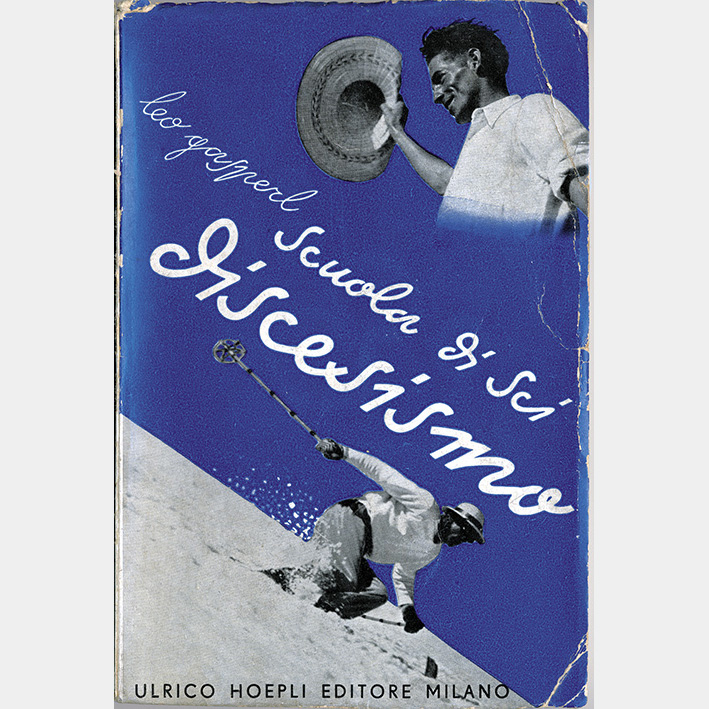

Starting from 1938 several of these photos were published in skiing magazines and were used to illustrate the skiing technique manual published by Gasperl in 1939.[^] Mollino signed a number of these ski photos, entrusting them with the status of artworks, while many others were used to illustrate his own book on skiing techniques published in 1950, Introduzione al discesismo (Introduction to Downhill Skiing).

NUDES WITH A LEICA, 1956-1962

In October 1955 Carlo Mollino brought to an end his seven-year-old love story with the sculptress Carmelina Piccolis,[^] the most significant of his entire life. In that moment Mollino probably realized that his time for getting married had expired and that he would never have a family, something his parents, hoping for descendants, had nagged him about constantly.

The following spring Mollino set out on another project, tackling the long artistic tradition of the nude, and explicitly confronting erotism.[^] In his Messaggio dalla Camera Oscura (Message from the Darkroom) Mollino had written:

“It is certainly not out of lasting habit that also painting of the last 30 years, launched on the most adventurous metamorphoses of visible reality, has continued to set its easel before a naked woman albeit forced into the most acrobatic contortions.”[^]

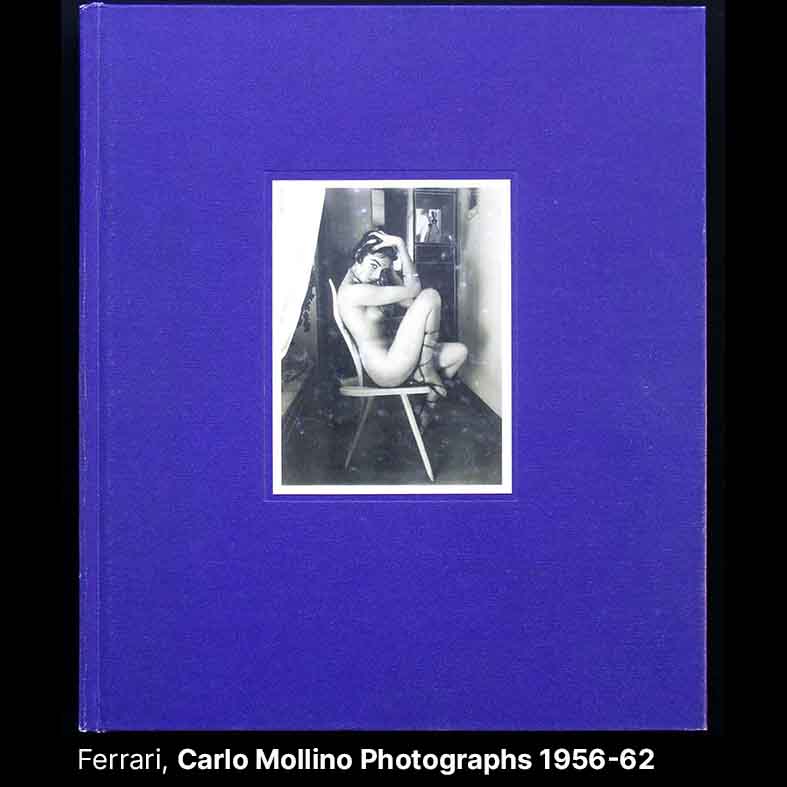

In parallel with Mollino’s photography, his friend painter Italo Cremona also focused on nudes[^^] in the 1950s.[^] Today we can place the 1950s corpus of Mollino’s photographic nudes in an intermediate point between classic B&W nude art and pornography, namely a new genre in the history of photography.

As usual, his preparation for the project was painstaking: he rented a tiny apartment on the hillside of Turin which he refurbished to look like an apartment and to serve as a photographic studio; then he began to buy (and continued to do so over the following years) the amount of women’s clothing he needed for his models, such as shoes, stockings, lingerie, gloves, wigs, hats.... The models were not professionals: some were friends, others orbited in the world of classical ballet or nightclubs.

So began a period for Mollino of sleepless working nights photographing and producing several hundreds of prints up until 1962. Using a Leica IIIb camera and mostly color negative films he has left us albums full of contact sheets that today allow us to follow the progression of each single photo session, which evolved for hours at night with Mollino constantly changing the women’s clothes and positions.

His trusted friend Montanaro would print the negatives selected by Mollino in his shop, all in a 10x15-centimeter standard format, after which Mollino oftentimes would further meticulously retouch the prints with a small brush, redesigning the bodies and their clothes and accessories.

In the end these photos were carefully ‘built up’ step by step. Mollino conceived them with an eclectic eye, freely looking at contemporary fashion photography or at the art tradition of ancient painting, sculpture, and everything in between. These images are utterly refined and formally of great beauty and aesthetic quality; they reflect a consideration of the classical beauty that Mollino soon desired to break with in his following work with the Polaroid.

Mollino never signed any of these photos nor exhibited or published them; instead, he used to keep the most beautiful of them mounted in albums which were shown only to a few friends, some of whom also received New Year greeting cards made up of one retouched photo. It was only after his death that the photos were published and became public domain.

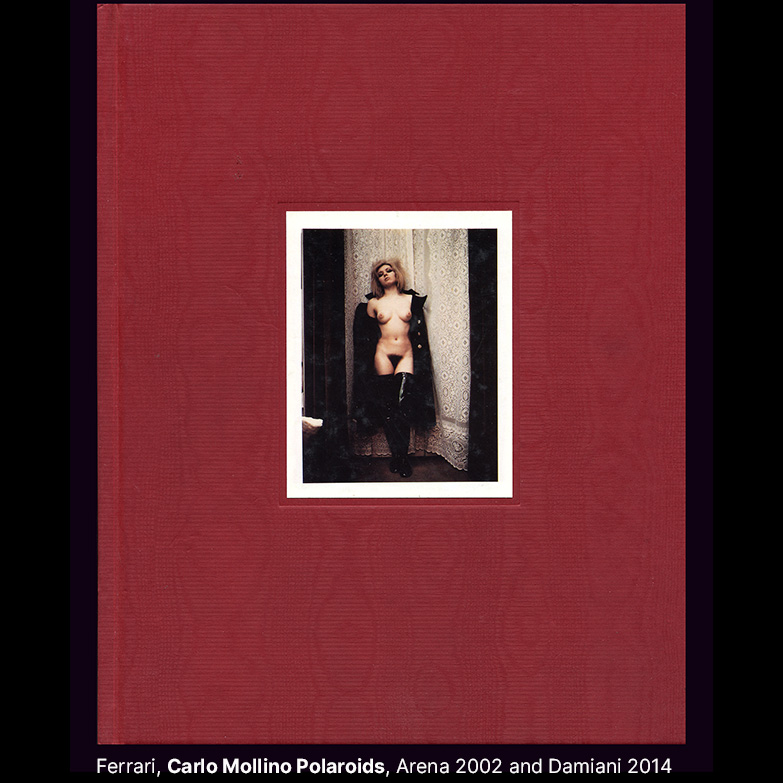

POLAROIDS, 1962-73

In September 1962 Carlo Mollino left the apartment used until then for taking photos and created a new photographic studio inside a small villa, once again on Turin’s hillside, that he bought and baptized Villa Zaira.[^] The place was beautifully isolated with a spectacular view of the city at its feet.

Mollino continued his search for women’s clothing, updating his wardrobe for his models to 1960s fashion, purchasing leather and plastic dresses among other things. And he moved on to use the new Polaroid camera,[^] abandoning the negative film. He undoubtedly loved the immediacy of the Polaroid but also the inimitable ‘mellow’ quality of its colors and the thick cardboard on which thin Polaroid film was mounted, making the Polaroids look like little objects. Once again Mollino was a pioneer and among the first artists and photographers to experiment with this modern technology.[^]

In approximately 10 years of work, he took over one thousand Polaroids, a small part of which were also retouched with the aid of an extremely fine brush due to the minute size of a Polaroid and by using a loop fixed on eye-glass mountings, making this work similar to that of medieval miniaturists.

Through the lenses of the Polaroid camera his models took on a more realistically crude appearance far from the beautifully idealized look of the 1950s: women were now pictured as actual girlfriends, wives, with their physical imperfections and individuality to make them more intriguing and genuine while, in parallel, the setting and background of the photos became anonymous and neutral.

This time-consuming and expensive activity was conducted during a very busy moment in Mollino’s life, and in parallel with the construction of the Chamber of Commerce, the Regio Opera House and Mollino’s own apartment in Via Napione, all in Turin.

Polaroids seem to respond to a number of vital issues relating to Mollino’s life, interests, and psychology: we can recognize a sort of melancholic[^] quest for a companion; Polaroids are an aesthetic search into the complexities of erotism which fundamentally relates to the function of reproduction of the species and for this reason is one of the founding mechanisms of the human psyche; they give form to the feminine side of Mollino’s personality embodied in his models; they also stage the man-woman social game of the relationship.

In search of a meaning for this complex and protracted effort pursued with the Polaroid camera we can surely borrow the words that Mollino had envisaged for Man Ray back in 1949:

“He looks upon things and persons, bowed and discerning, like a mad entomologist and from behind the screen of professional earnestness he almost takes pleasure in what is revealed by his gushing light of desire, in what a surprised and defenseless face unconsciously offers of its grace or misery, in an anatomized nudity, in front of an inner strength or just a presumption. All this could seem meaninglessly cruel if his desire were not always fused with mercy, a mercy born out of a profound and clear understanding of the mortal weakness common to matter and to our senses. Seen through his desire, humans and things suffer and reveal the same fate.”[^]

Museo Casa Mollino

Museo Casa Mollino